Nichijou Beyond Comedy

I was introduced to Nichijou around 2014, by a friend who would eventually share their love of what we now like to call “mellow anime” – Laid-Back Camp, New Game, Long Riders, A Place Further than the Universe, Is the Order a Rabbit?, and the list goes on.

Crucially, even this selection of titles is actually modestly diverse. Most are labelled as “slice-of-life”, but the subgenres range from comedy to sports, to iyashikei – “healing type”. I would only find out about the latter term in my research for this, but I think even trying to link the iyashikei or slice-of-life terms to some of these titles dilutes their meaning, and really doesn’t get to the heart of how we thought all these felt “mellow”.

It really comes down to more than just what a show is on the surface. It’s something that transcends culture, transcends the moment, and seems to only get more clear as our means for telling stories evolves.

Nichijou will be my way in, to tell you just what that is.

The Surface Elements

Read any material, or watch any video, discussing Nichijou and they’ll all put the comedy front-and-center. And rightfully so, of course. To foreign eyes, a lot of Nichijou‘s humor just soars right into your face. Your first impressions are likely just… what? The anime especially, it bounces seamlessly between static, doodley figures and high-octane action sequences – ones ultimately signifying nothing, right?

Two schoolgirls fail to smash an unripe pumpkin. A robot girl not only exists, but physically embodies the whims of an even younger girl. The wide array of side characters get their own wacky subplots. It’s a weird anime, right?

Well, let’s try and make sense of it.

This Japanese suburb – actually based on Isesaki, in Gunma Prefecture, where creator Keiichi Arawi apparently grew up – is rendered quite idyllic. Nano Shinonome is followed around by a light, tender score made partly in Hungary by second-string Studio Ghibli composer Yuji Nomi, which is soaked in acoustic reverb but doesn’t get too bombastic even in the high drama.

In a medium that’s long been shorthand for fanservice and exploitation, the characters are treated rather sweetly, with even the most heated conflicts only passing. Mio Naganohara draws yaoi of her crush, but the most any lady gets that treatment over is one guilty teacher picturing another just chilling at home.

Nichijou has a lot it doesn’t touch on. In fact, not much of its setting really feels modern or cutting-edge.

The Contemporary Touch

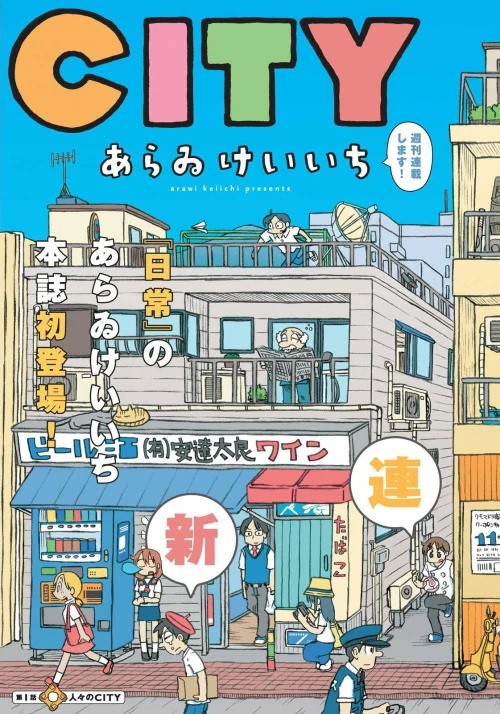

To show you what I mean, I have to bring up Arawi-san’s sequel manga, CITY.

Billed as being in the same universe as Nichijou, CITY takes place in what’s meant to be a more sprawling city than the unidentified suburb in its predecessor. However, the city that it’s ostensibly based on – Wakō in Saitama Prefecture – is actually smaller and denser. Despite it being right on the border of metropolitan Tokyo, there’s a separation from the metro culture that the manga nods to.

As you read and understand the manga, you realize that the city named City in the manga CITY is really just a picturesque town that just happens to have more to do.

Nichijou and CITY each have just one featured police officer. City’s local newspaper is both tiny and bankrolled by a local heiress with a story rivaling Mio’s daydreams of the Fey Kingdom. Much attention is given to photography and manga-drawing.

One thing CITY has over Nichijou is a more diverse cast. The center of the action is a western-style restaurant, owned by a guy with a classy Mediterranean mustache. The newspaper’s mangaka at the start is a perpetually sad guy with a beret.

We’ll have to see how well the likely anime adaptation goes, since CITY is wrapping up now, but it’s proven to expand on what makes Nichijou‘s setting tick – it’s familiar and grounded, without making anything about its location or time period stand out very much.

The music as well – we mentioned Nichijou‘s score, but its two theme songs by retro-pop musician Hyadain hit right at the ceiling of appropriate instrumentation, and yet feel more like a frantic nostalgia bomb. They get away with a similar mix of chiptune, orchestra, and acoustic sounds that a lot of soundtracks in Japan have, but they’re also written like ascended playground songs that jolt you into the spurts of randomness that Nichijou peaks at. They certainly give me chills every time I listen.

The ending songs do as well. The versions of the first ending embrace the imagination side of Arawi-san with a lullaby rendered in lo-fi flavors. The second set of endings is populated with a whole medley of acoustic tunes sung alternately by various soloists and a choir of little schoolkids, in a way that’s quite sobering in comparison to the first.

Also, if you watched Nichijou, did you notice a lack of mainstream metro-Japanese culture – idols, music, films, consumer tech, gaming? At least, no greater than rare cell phones and computers, both taken for granted today. Some of it shows up in the margins in Nichijou, but often in contradictions. Nano is outfitted with CD and USB support, but she also has a giant wind-up key. Mai plays a Famicom on a flat-screen TV. Yuuko draws Superman.

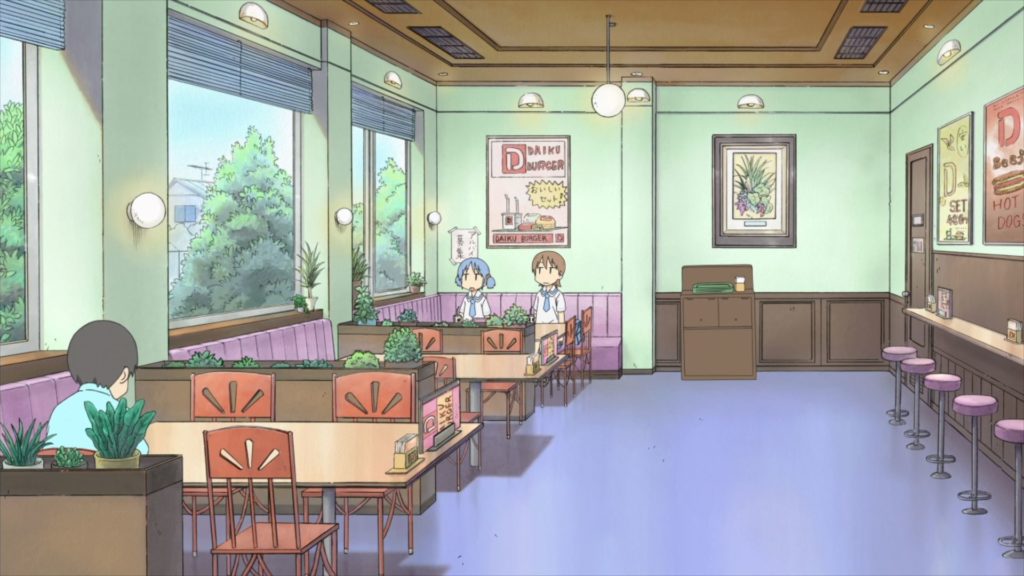

In fact, more attention in Nichijou is given to foreign culture – especially in the English language – and how the characters react to it all. In the case of Superman, it’s a given detail, as if including a fairy tale. But there’s also chain restaurants Daiku Coffee and Daiku Burger, where an extended plot is given to Yuuko and Mio over being able to read the coffee menu. In the Funimation dub, it’s treated like learning Starbucks lingo for the first time, but the paired Daiku Burger scene is a minimally-spoken reinforcement of the bilingual disconnect.

Of course, Nichijou plays just as much with Japan’s traditional culture, down to local Shinto traditions. If you watch a lot of slice-of-life anime, the customs are a given, and really only the practical side of real life is explored. After all, these are made for Japanese audiences. However, Nichijou spends a lot of time with shrines, kendo, honorifics, and various superstitions. In fact, a watchful presence at Shinonome Lab is a Daruma doll, which popularly has its birthplace in nearby Takasaki. More than that, the second half of the series uses credits over long tableaus of the city, rendered in a near-isometric perspective reminiscent of traditional ukiyo-e art.

The real implication is that pop culture and technology have slowly trickled down into the suburbs, where it mingles and sometimes clashes with local traditions. You may recognize the trickle effect in something like Napoleon Dynamite, except that movie aches to draw attention to its anachronisms through style. Nichijou does use style as well, but it prefers to draws attention with a different technique.

The Collage Format

In 2007, Kyoto Animation released the anime Lucky Star, one of the first real breakout hits in the slice-of-life genre. Along with Azumanga Daioh before it, Lucky Star codified the slice-of-life formula, but also did it with a such a thick layer of meta-commentary that it fit right in with the Shrek generation across the Pacific.

It had everything modern – cell phones, emoji, fanservice, video games, manga. It even channeled Clerks energy in how characters spent long stretches of time talking about random things. It was everywhere. In fact, I’d always pass by an animated billboard clipped from the intro, when playing in the meme-stuffed Team Fortress 2 mario_kart map.

Even so, it has a pretty straightforward format. Each episode is a cohesive whole, with little straying from the main characters – aside from the iconic “Lucky Channel”, a bitter twist on silly omake segments in even serious anime. To succeed, it had to be traditional where it counts.

Nichijou, on the other hand, is quite an inverse of the whole concept. Rather than a winking meta-commentary on its own existence, it’s a more straightforward tableau that allows its expanded structure to be the vessel for its commentary.

The meat of the scenarios comes from the same typical manga and yonkoma – four-panel gag – formats that Lucky Star does. Larger segments are numbered, while short ones are given a topic as a title.

Paired with it, however, is a random-seeming collection of recurring segments that vary wildly in tone: “Short Thoughts” is a catch-all segment of internal monologues sometimes related to the plot, and only occasionally throws a joke in. “Like Love” and “Little Miracle” are almost entirely sweet and unfluffed. The characters will also do a bunch of short games and topics in a white void. “Helvetica Standard”, the manga within a manga, is really a vessel for the unfiltered raw style of Arawi-san, but we’ll get there.

Even the interstitials – of which the fan wiki somehow sticks to the logo-bearing ones – are quite diverse. The logo-bearing ones are mostly animated Arawi doodles, which I’ll also bring up soon. Other ones are rendered like security cam or documentary footage, pointing clinically at some angle of the same world, without any of the comedic visual detail, and with no more than ambient noise in the soundtrack. Those two approaches alone are utterly contrasted with each other, but inform the same truth about the world of the anime.

Empty elevator. (Episode 22)

One set of doodles riding another set. (Episode 24)

The Storybook Factor

We talked a bit about the connection between Arawi’s fictional cities and the real cities they’re based on. Lucky Star actually helped spawn a wave of media tourism to cities featured in anime prior to that, as did yet another Kyoto Animation series – K-On! – but Nichijou was arguably late to the party.

But then again, unlike its older series siblings, it made up for it with a different attitude toward its own existence.

Think about where those budget-blowing sequences exist, in the context of the characters. Hakase, the toddler inventor, gushes emotion and imagination, but it mainly manifests in her inventions, which take on a life and role of their own. Nano is both modeled to be a human teenager and installed with things that play off her reactions.

Speaking of little kids, they’re rarely shown to have influence over the show’s reality. One “Little Miracle” scene shows a girl winning a class jan-ken for the last dessert at lunch, and the others applaud in cordial awe. To me, it feels like a reflection of school molding children at a young age, and how children soak in life at face-value just as much as they put it in crayon.

As far as the other main characters go, Mai, Mio, and Yuuko are the least to most emotional, in that order. Yuuko will react to pretty much anything in excess – it’s when she runs dry that’s remarkable. Mio is more collected, except in her specific embarassments, and it plays into her athletic clumsiness. Mai, on the other hand, exudes influence when she speaks, and shapes the reactions of nature and other people instead of her own reality.

Think of this element like Scott Pilgrim with no stakes – just a bunch of teenagers expressing their emotions through a filter of drama and action that doesn’t always make sense.

But that’s glossing over the fact that these are ultimately drawings.

The Imaginative Side

Arawi-san likes to post doodles on Twitter, and animated shorts of the same kind on YouTube. They’re very much one and the same with the logo interstitals, with a blending of everyday object studies, cartooned versions of religious and cultural imagery alike, and a seamless mingling of imagination with nature.

For instance, the bird doodles are given names like kumomadori (used as his brand name) and mogura, plus the smiling spoked-sun is named a kamakura.

Those animated shorts, I’d argue, do a much better job explaining his creative process – because they actually spell it out quite plainly.

Thankfully the lyrics of this one were translated into English captions, so they can be followed along rather easily.

Okay, you artists who post online. You can relate to this, right? Maybe not explicitly to deadlines, if you’re still a young artist doing your thing for fun, but there’s that persistent grind. Animators as well – if you’ve sworn by The Animator’s Survival Kit and do a lot of life-studies, you’ll see it’s quite potent here.

The actual imagery isn’t really all that “weird” per se – it’s no more abstract than a lot of what goes into Mario games – it’s merely his specific vision that filters the real world through imagination, emotion, and artistic impression. Just like Hyadain’s theme songs, they blend a lot into a tiny package. And just like Hyadain, who got his big break on YouTube, Arawi-san’s art feels right at home on social media.

In Nichijou, it’s all there. It’s just not as obvious through the persistent need to feel like a grounded slice-of-life. It comes out the most through the logo interstitals and “Helvetica Standard” segments.

The Generic Uniqueness

In 2005, NBC began airing The Office, an adaptation of the hit British mockumentary series. Despite early mixed reception of the imported mean-spirited humor, it became a smash success. Two years later, Valve released Portal, a first-person puzzle game with a concept so hard to fully explain to new players, that virtually the whole game is structured as one giant tutorial. Nowadays, with Portal 2 being a massive follow-up, the concept is intuitive to players of all ages.

The way both of these titles succeeded is the same ingredient that made Nichijou special – generic signifiers.

Portal and The Office both use generic signage as inseparable parts of their branding. Their almost un-trademarkable titles set baseline expectations that are more than exceeded with the quirky details hidden within. Characters start out as one-note archetypes of a familiar setting, and they gradually form dimensionality over time.

Nichijou, in my observation, is playing very much the same game.

The setting is, to fresh eyes, a nondescript suburb with a high school. The schoolgirl clique we follow around is a familiar trio – the brash one, the smart one, and the silent one. Ignoring the robot nature, Nano is really just an older sister taking on house duties. That’s enough to be a rather boring slice-of-life, but it’s merely the baseline expectation.

That baseline expectation is heightened by the use of possibly the most generic font for its rōmaji title – Helvetica. Yeah, I went there. “Helvetica Standard” is really just that generic uniqueness turned in a different direction. Its contents are directly from Arawi-san’s stream of consciousness as in his animations, just in yonkoma form. It’ll show angels making toast, demons trying to speak, grim reapers being awkward, cute animals being late on rent, and so on. It’s a respite, though not a total escape, from the tangibility of real life.

The Impermanent State

One thing that both the previous factors have in common is that when they’re put on paper, they become paradoxically a fixed record of impermanence.

Impermanence is simply the philosophical idea that nothing ever stands still – things will always change. In Japan, a person’s internalizing of impermanence has a term – mono no aware. Most languages have similar terms and phrases, tapping into the long-term melancholy of realizing life is meant to pass. In studies of Japanese culture, it’s most applied to work that is explicitly drama-focused, though there are other ways for it to be expressed.

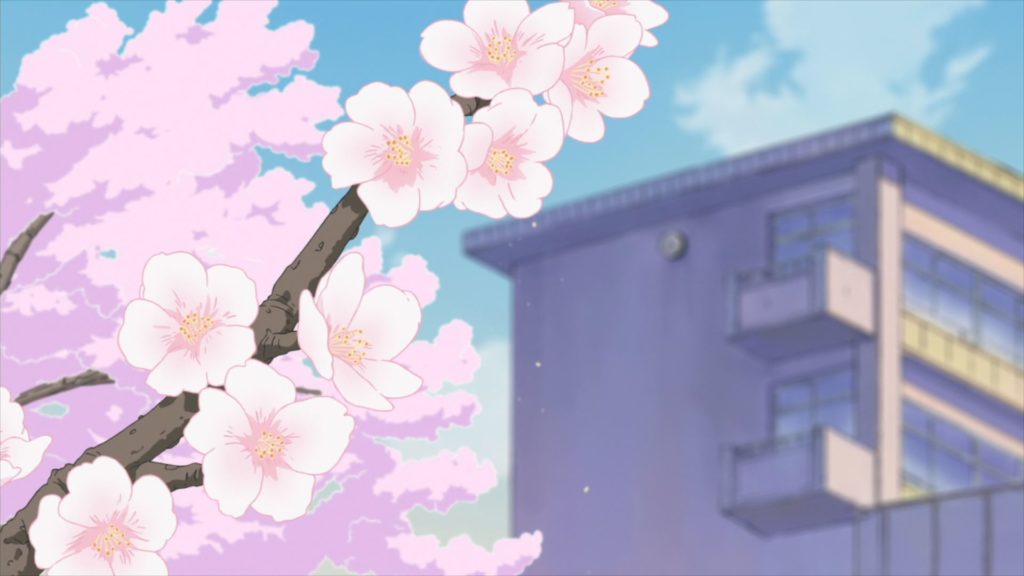

For instance, cherry blossoms only bloom in a very narrow part of spring, and viewing them is a cultural tradition explicitly tied to their association with this concept. Nichijou begins the first episode and ends the last with a poetically similar scene about motivation for school, where cherry blossoms pop out with the punchlines.

Other analyses of Nichijou do tend to touch on the impermanence angle, but only as a late addition to their conclusion. So I wanted to give it a bit more context here.

While we’re here, let’s touch on the iyashikei subgenre, which I briefly mentioned at the start. Major sources of what counts in it disagree on whether earlier works like My Neighbor Totoro are included, but Paul Roquet suggests it properly started in 1995. That year, the Kobe earthquake and Tokyo subway sarin attack traumatized the country, which was already deep within the Lost Decade recession. A volunteer movement rose after the earthquake, and affected families found therapeudic entertainment.

You might know about some entertainment in that vein, especially now in a COVID-affected world. Animal Crossing is commonly considered a self-care game series. I’d argue that while Nichijou isn’t really a healing anime, it’s very much steeped in the impermanence that creates a similar feeling.

The Ultimate Contrast

Now that we have these elements in play, let’s get right to the intent. Nichijou is an exploration of life filtered through multiple lenses, and does so through contrast.

The show itself is a largely tender look at life in suburban Japan, gracefully hovering between nostalgic and modern, and also between different layers from realistic to fully imaginative. They are memories being shaped and compounded in real time, by everybody.

Those layers tell a story about each character, in a way that allows for such a massive ensemble compared to other series. Not only do they have thoughts and motivations, but how deep their thoughts go can say a lot more about the kind of person they are.

You instantly get how each individual participant of the famous Igo Soccer match feels, thinks, and even knows about the sport, despite not being told a single thing about how it’s supposed to work. Incidentally, Arawi-san is quoted as saying it’s “kind of like jazz.”

The All-Important History

I tend to divide up phases of east-west cross-pollination in a certain way, specifically starting with the rise of imports and outsourced animation in the 1980s. There’s long been a give-and-take relationship that doesn’t necessarily affect the business models of each country’s animation houses directly, but it certainly created a wave of back-and-forth evolution.

Let’s take the early 2000s for example. Anime was at commercial peak with franchises like Pokemon, Yu-Gi-Oh, and Naruto taking over western airwaves, and the response ranged from Avatar: The Last Airbender to Totally Spies. But even so, other anime imports were spreading through DVD and gaining online fans, returning extra money to those animation houses.

Nichijou was on the crux of a transition at the start of the 2010s, for both cartoons and anime. In America, a second wave of incubator projects sought to collect fresh talent, after spending a decade with the Cartoon Cartoon generation. In Japan, the government contributed to the Young Animator Training Project, which in 2012 funded the creation of Little Witch Academia.

In the grand scheme of things, it means that Nichijou was too early to be appreciated, but it does serve as a useful milestone marker for comparison. For example, we’d soon get shows like Adventure Time and Steven Universe, bringing forward supportive messages and even LGBT representation. And while newer anime are still known to indulge, a larger proportion of them were made and seen in the 2010s to reflect similar tones to Nichijou.

Laid-Back Camp and Long Riders are two examples, where they portray hobbies close to nature with a supportive and positive community. New Game brings the rosiest possible look into game development, showing a near-utopian vision of a company that still deals with things like crunch and crediting. Their quality is beyond the scope of this article, but you get my point.

I’d also be remiss not to bring up the tragic arson attack at Kyoto Animation. Beyond the heinous act itself, there was a great outpouring of international support that reminds me of how loving and positive the anime community has become in those later years. I’d give credit for that to KyoAni for everything they did in those crucial years making Lucky Star, K-On, and Nichijou.

The Final Verdict

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this journey deep into a show that I figured most people would take at face value. Since this is still early in the publishing life of Pop History, I wanted to broaden the reach of the site early and give you, the reader, the chance to sample dives into a few different mediums.

I’ve gone out of my way to avoid talking about the comedy as much as I could, but it’s still woven into the premise. The title is ironic, yes, but the reason for it being ironic to me is more interesting than just pointing out that it is.

It’s because despite the actual content of the manga and anime having a lot of strange, abstract, and unspeakably hilarious moments, it still anchors itself to a set of basic truths – life is built on top of reality, shaped by each person’s developing prism of emotion and experience, and faced by outside changes and pressures often out of their control.

Those changes can be cultural, interpersonal, anatomical, or political, but they’re all temporal. Life can’t be stripped to its essentials, but by embracing the ways you can make sense of the world – through creative expression and friendship – then you may just have a foundation.

Reality + imagination = life. That’s what Nichijou is about.