Rugrats at 30: Grown-Up and Revolutionary

I was going to title this “The Adult Animation Roots of Rugrats”, but I don’t want you to misinterpret – Rugrats is not a show conceived in spite of kids. It was very much pitched with the understanding that Nickelodeon was seeking to cater to a new generation of children. However, that generation was being raised with a new curriculum that many kids in the prior decade were not – they were raised to be rebellious and freaky, and to embrace it.

While Rugrats was not the most irreverent show even among its own brethren – it co-premiered with the controversial Ren & Stimpy, after all – it was nonetheless the same vessel for introspection that its creators and their colleagues were made famous for.

Legends of the Dark Age

Animation history as it’s written today tells of animation being in a slump throughout the ’70s and ’80s. Despite efforts by Disney to hire a new generation of animators, primarily from CalArts, the dwindling quality and reception of their films at the time meant that other studios came up to sell themselves as modern alternatives.

This legend points out that the prospects were very different on television versus cinema. While television was dominated by low-budget kids fare from Hanna-Barbera and their spinoffs, theaters and video stores could stock up on risque content, ranging from imported anime to the latest from studios like Nelvana and directors like Ralph Bakshi.

Finally, the legend says the age was lifted with the great war between Disney and Don Bluth, coaxing a rapid rise in quality that blossomed with the Disney Renaissance, lifting everyone else up into enlightenment.

There’s truth in that legend, of course. But the reality is, more opportunities were abound for those who knew where to look.

The Exceptions

The first big exception to the television wasteland was MTV. While it wasn’t quite as unhinged in its early days at it would be a decade later, nor was it even all that widespread before national cable, it was a channel where animators could get their work seen. Through music videos, commercials, and occasional bumpers, it was a venue where animators could let loose and be able to say on their demo reels that it aired on television.

Alongside that, some industry veterans took part in underground activity – animation festivals and tape circulation. Spike and Mike’s Festival of Animation especially was a big recurring venue for talent, and that’s a whole topic of its own. The recent documentary Animation Outlaws goes into the origins and memories of that festival, which was often the first inflection point for animators like Craig McCracken, Andrew Stanton, and Danny Antonucci.

Those animators were brought into an environment where they were allowed to embrace the rough edges, and have fun being less than child-friendly. Spike and Mike’s especially was that kind of environment – irreverent and fun for grown-ups.

The other big exception came late in the decade, with the emergence of Fox. In 1985, Rupert Murdoch separately bought 20th Century Fox and a chain of independent TV stations with roots in the failed DuMont network. After a year of setup, followed by another six months of soft-launch woes, Fox debuted the first of a surprisingly hefty primetime lineup. While animation was not a real presence – it was mostly title sequences using them – there was one standout.

One Big Break

Paul Germain told his story to the Nick Animation Podcast, in that he lucked into working as a production assistant with producer James L. Brooks on the film Terms of Endearment, which eventually led him to blunder into being in charge of animating a recurring segment in The Tracey Ullman Show.

At the time, the original Saturday Night Live generation had blossomed into feature films and sorted themselves out, leaving television with a hole ready to be filled. Pitching Tracey Ullman as a multi-talented comedian able to hold up a full show was bold enough, but to fill out where the flow might’ve slumped, that led to the well-known involvement of Matt Groening, to create The Simpsons.

But more than that, trying to find a studio to properly animate the show led him to discover Gábor Csupó, a Hungarian animator who became the face of local studio Klasky Csupo. As Germain recalled, “It turned out that all those animations were done by a bunch of young people that Gábor had hired to come and do some of them. He hadn’t done any of them. They were all student films from from CalArts and UCLA and places like that.” Aside from that discrepancy, Csupó’s distinctly Frank Zappa-influenced outlook certainly matched his team’s decision to match Groening’s rough storyboards and animate it more crudely in its early years.

It even carried over into the standalone series. In fact, people might recall the clip below circulating around as a hilarious example of the animation being inconsistent. The switch from Klasky Csupo to Film Roman in 1992 is a small part of Simpsons meta-lore within hardcore fans’ own deeper opinions about when they think the show went downhill.

Development

Germain claimed to be unhappy in his production roles at Gracie Films, and took on an offer by Csupó to work in development.

While there, Nickelodeon had brought on Vanessa Coffey – who produced an animated Thanksgiving special for them in 1988 – to launch Nicktoons, an initiative to bring original animation to the cable channel. Coffey separately took a chance with struggling animator Jim Jinkins pitching his character Doug, as well as animation veteran John Kricfalusi.

Let’s get this out of the way. John K would’ve been a much better case for an “adult animation roots of a kids show” article, but with the twist of the show being almost too far from the outset. However, his later reputation almost speaks for itself, and the troubled production of Ren & Stimpy – despite it being very successful and influential in its own right – almost certainly stumped its own potential.

Even so, the same lessons that would’ve been done with Ren & Stimpy against later shows do still show up in Rugrats, so we’re not without all that.

So after the pitch came the pilot, which put together a lot of ingredients.

Peter Chung – who was still a year away from debuting Æon Flux – was hired to direct the pilot and co-design the characters. Csupó’s influence was to make the babies “strange rather than cute”, while Chung’s hand in storyboarding and layout set the stage for the signature low-angle, fisheye-warped approach that would be seen in the famous title sequence.

Mark Mothersbaugh, who was on for the seemingly-last years of the boundary-pushing band Devo, had just started a music studio called Mutato Muzika. The Rugrats pilot was one of his first assignments, and the raw synth-programmed melodies he put together would create an appropriately childish atmosphere, with a twinge of his avant-garde sensibility.

To round out the series going forward, the team created Angelica, quite possibly one of the most memorable antagonists of that era. So memorable in fact, that figuring out how far to push her bullying nature created the main conflict among the writers – especially Csupó’s then-wife Arlene Klasky, who reportedly hated her – moving forward.

The Show Itself

Much like its half-sibling, The Simpsons, Rugrats got a lot of attention for Jewish representation. Arlene Klasky was Jewish, and pushed for an inclusive family that was part Jewish, part Christian by marriage. Two specials themed around Passover and Chanukah were the only new episodes in the midst of a hiatus in the show, the first having been made by the original writing team.

Despite the praise those specials got, the appearance of Grandpa Boris in a later comic strip drew ire from the ADL for being too close to Nazi-era stereotypes.

Aside from that, the show tackled a lot of cultural mainstays from the beginning.

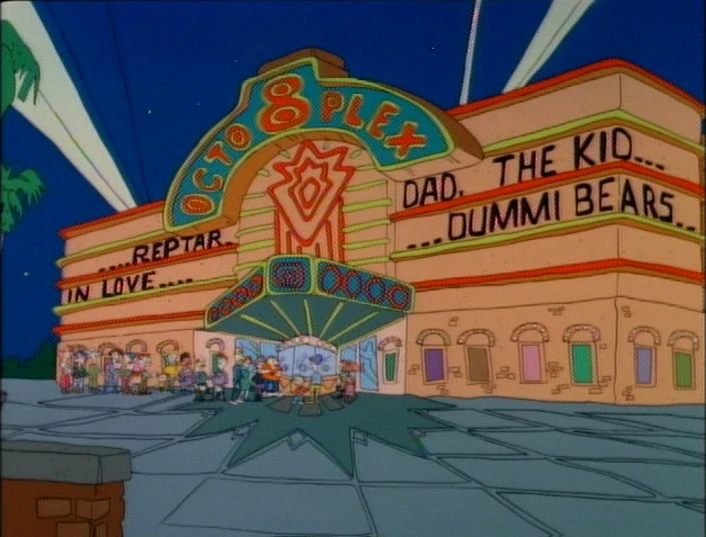

Just for one example, my personal favorite episode, “At the Movies”, tackles a bunch of movie types at once. It’s famous for introducing Reptar, at a time when Japan was just tipping off the economic cliff, but choosing the movie the family goes to see – The Dummi Bears in The Land Without Smiles – reads very much like a bitter catharsis for an animation studio finally “getting revenge” for animation being taken over by low-quality cartoons. In the legend of the Dark Age, this is calling out The Care Bears Movie for beating The Black Cauldron at the box office.

Reptar would eventually be the writers’ vessel for more parodies, including ‘Reptar on Ice’ and “Runaway Reptar”, with a hand-made Reptar wagon being a centerpiece prop of The Rugrats Movie.

Beyond that, I believe Rugrats found a very unique tone, balancing delicately between slice-of-life sitcom and mini-adventure story in a way that few animated shows up to that point could handle.

Having a language barrier between the adults and babies divided their scenes up nicely for the show’s dual audience, and while the characters were certainly designed “strange” by real-life standards, they remained thoroughly appealing, and set the standard for balancing character design. As much as Ren & Stimpy inspired reaching for the extreme, Rugrats reminded artists the value of starting from cuteness.

Having it be slice-of-life with reasonably natural characters – talking babies is the main stretch – also allowed those babies to do more than just receive lessons or go on fun adventures. No, they were allowed to be involved in everyday situations and even realistic drama. The Mother’s Day episode addressed death in a way that stands with Sesame Street dealing with the passing of Mr. Hooper in top all-time children’s episodes.

The Legacy

I’m probably one of the few people in my line of work who both remembers Rugrats and wasn’t all that upset with the announcement of the new 3D reboot. Yes, it was sanitized from its rough 2D roots – owed by being animated by Technicolor Animation Services, who also did the meme-worthy Sonic Boom – but the core creative trio remained involved for this one. Mostly, I was just uninterested, and at least hope that children with fresh eyes enjoy what’s there.

The thing is, Rugrats changed over time, and left the world as it continued to evolve. The same animation scene that allowed Klasky Csupo’s line of shows – Aaahh!!! Real Monsters, Rocket Power, The Wild Thornberrys, Duckman, and others – eventually transitioned all at once into a digital pipeline, embracing more dynamic shows across the board.

Even when the Rugrats movies came around, they rounded out the characters and made them a very different ensemble from when they started. They even gave Klasky an Angelica she could finally enjoy. The challenges, of course, would continue with the sequel series – All Grown Up! – where just the right amount of growth had to be found without turning them into full-on teenagers.

The real legacy, I think, is in how Rugrats set down a solid tone for a slice-of-life series. Ed, Edd n Eddy, created by fellow adult animator Danny Antonucci, is probably the closest similar show in that regard, but other shows from Courage the Cowardly Dog to Codename: Kids Next Door would treat their dual-reality adventures differently to shows before Rugrats, blending them meaningfully to create stories using the best of both worlds.

As for adult animation itself – let’s just say they’ve been worse off making too much of a distinction.