From FMV to MMO: Virtual Magic Kingdom’s Second Life

After the shutdown of Virtual Magic Kingdom and the eventual 1999 release of Disney’s Villains’ Revenge, Disney Interactive was in shambles. The unit’s final in-house projects were finished, and their pivot to fully outsourced games was more or less complete.

Roger Holzberg left DI early in the decline, transferring over to the other DI – Disney Imagineering – along with a number of his previous coworkers. As the most senior person of the division by the time he left, he had status within the company.

In this polished excerpt from the upcoming Virtual Magic Kingdom interviews, Roger Holzberg recounts his story on how he helped run Disney Parks and Resorts Online, and revived Virtual Magic Kingdom into the beloved MMO game.

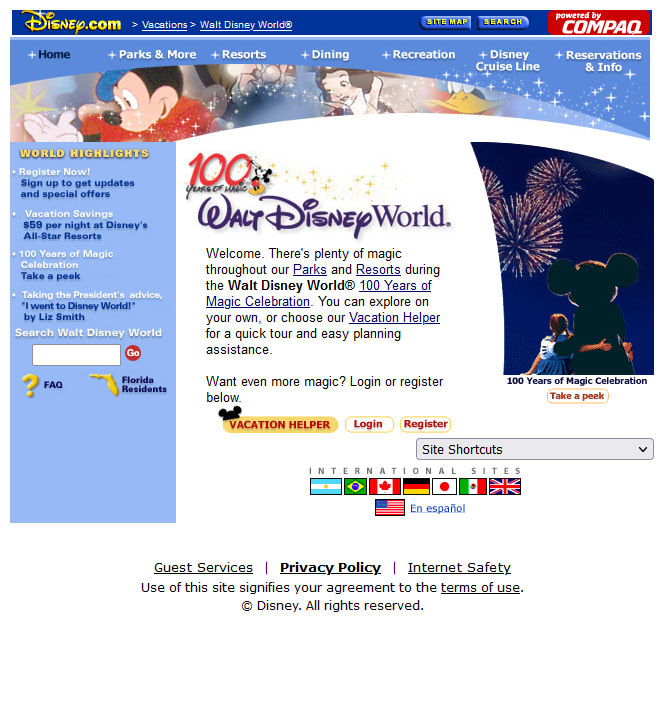

I was largely on the Walt Disney World portfolio as VP/Creative Director, and over the portfolios that had to do with the Millennium Celebration, and then the 100 Years of Magic celebration.

And then 9/11 happened. And 9/11 contracted the world in kind of a mini version of what COVID did.

When 9/11 happened, about the kind of layoff that happened at DI happened at Imagineering. Because it was very clear to everybody that nobody was going to be travelling to the theme parks for a while, because nobody was gonna be getting in an airplane for a while. So about three-quarters of Imagineering got laid off.

Paul Pressler, who was president of Parks and Resorts, decided to take a step back and see what it was like to book a vacation online to a Disney resort. And [he] realized that booking online at Walt Disney World was entirely different than online for Disneyland. Not only was it entirely different, you had to create a new account, an entirely different user interface, an entirely different guest experience. There was no immersive media.

And he went, “Okay, I don’t know anything about making software or selling anything online, but I know what I’m doing is wrong. So we’re gonna put together a new division of the company, and have a hybrid between Imagineering and Disney Online, and we’ll call it Parks and Resorts Online. So who can we get from Imagineering? Oh, well there’s a VP/Creative Director who used to make video games. He must know about online stuff.”

We staffed Parks and Resorts Online to up over a hundred [people] in six months or so. It was crazy. And the beginning work was the block-and-tackling work of: Okay, the booking engines have to sync up. The user experience has to sync up. If you create an account at Walt Disney World, and a year later, you want to go on vacation to Disneyland, you’ve gotta be able to log into the same account and book your vacation there. Right? It’s like Online Commerce 101. However, there were 25 thousand legacy pages of Walt Disney World from 18 different resorts, for theme parks, a cruise line being concepted in the early days at that point, sports complexes. It was every bit the effort that VMK was, right, just to make it usable.

And then phase two of Parks and Resorts Online was experiential marketing, which we took on with– and I will tell you, I absolutely used the rails-and-node concept that we used in VMK to build a rails-and-node engine for touring resorts, and touring rooms, and touring cruise ships, and touring attractions “virtually”. All of which was streamable finally at that point.

Phase three of Parks and Resorts Online was really kind-of next generation wedding of attractions virtually to attractions physically. So the first heavy-duty game we built that met that challenge was Buzz Lightyear Astro Blasters Online. [It] literally paired two players online in a synchronized rail-node shooter game with the ride at Disneyland, so that they were playing together, the virtual team and the physical team, to become the highest-scoring “team” in the universe versus players in the theme park. And then we did a Tower of Terror haunted computer game.

And we got smart, because we were looking for big budgets. This is where I had learned incredible lessons at DI. The lesson I didn’t know at DI was how to play the bizdev game. How to show the potential or reality of profitability, and show it in a way that the– ‘cause truthfully, the creative teams that were running the company in 1995 when we all went there and were working on that, were not running the company anymore. You had a business degree if you were running a division of the Walt Disney Company by 2004.

Posted on YouTube by Roger Holzberg.

So consequently, with the Tower of Terror game, we had redemptions in the parks. And every time a coupon was redeemed, we knew that we had driven a $100+ ticket price at a gate, and we could claim that as our own ROI. And so we knew, we had at least invented a “mechanism” by which we could say, “For every dollar spent creating an entertainment online, we believe and we’ve demonstrated that we can drive this amount of ROI in the theme parks.”

So, we took that kind of pro forma model, and we did a prototype of VMK as an MMOG. We knew we couldn’t build an engine. We knew we had to leverage an engine that was out there. And Habbo Hotel [from Sulake] out of Helsinki gave us that engine. They wanted to break out and become an international thing, versus a European-based MMOG, which is what they were.

So we built a prototype for, I wanna say $25,000. I’m not kidding. It was like nothing. And we took it to Michael Eisner. The company was still at that point where anything that cost over five million dollars – and we knew VMK was gonna cost more than that, over its three-year life cycle – was gonna have to get approved by him.

So we built an Adventureland prototype, which included a multiplayer Pirates of the Caribbean game, which was unbelievably fun and addictive and everything you want an MMOG game to be. You know, where you can form a clan, queue up with your own people, and go wipe everybody else out, and get rewards for it. And we went, “Okay, we demonstrated already that we can redeem these rewards in the parks. So we know we’re gonna drive business.”

So that was the pitch, right?

Fortuitously, Disneyland’s 50th was right on the horizon, and Disneyland had no significant online promotion to do for Disneyland’s 50th. And VMK became it. It was great timing, it was a great pitch, it was a great prototype, and we went heavily into production.

We launched the game with one land, and we rolled out another land a quarter later, another land a quarter later, another land a quarter later.

I will tell you, the one biggest lesson we learned– and you could only do this in an MMOG kind of game, where rooms are cloned and scaled as cloned, and you can have a million, two million, four million players in the game at a time.

So, Habbo Hotel was built on the idea [of] getting status and having status, and you’re cool if people come into your private room and hang out with you, and there was a chat engine where people could chat. It was dictionary chat, so no numbers and no obscenities could be used.

We thought we’d have a couple premier games in each land, and people would go out and play the premier cool games, and then they’d buy stuff. There were stores, and you can get virtual stuff. I started feeling really guilty when I started seeing props from VMK selling on eBay. There was a mom who spent $300 to get her kid a pair of green flip-flops that were very rare, and I was like, “Oh my god, what have we done?” And it was insane. There was an entire secondary business that we didn’t think about.

But that wasn’t the big learning.

So we thought we would do these setpiece games, like the Pirates shooter game, capturing ghosts in the Haunted Mansion, and we did these setpiece games. And players played them for a while, and then they got bored.

We had props that they could buy and acquire to get more status. I can’t remember whose idea it was. I wish I could take credit for it, but I wanna say it was probably Seth Mendelsohn. Said just, “Let’s try just having a prop that’s a dynamically number generating dice, where the virtual avatar can walk over to the prop, touch the top of it, the dice will spin, and then a number will pop up.” Great idea! We built it, we unleashed it into the virtual stores.

Two weeks later, there were baseball leagues in VMK, with rules in chat. You know, if you got 1, 2, 3, 4, obvious bases. 5 was a blah-blah-blah, 6 was an out, 7 was a double-play out, right. And we had picnic supplies, and people were making blank rules, and they would put plates down for bases. And we went, “Holy crap, we better make baseball props.” And we did, right? And all of a sudden, we had a baseball league.

I’ll tell you what we learned was: Providing the tools to make games, and letting our players create the games, delivered exponential levels of gameplay that we never could have done in-house. And levels of addictive gameplay that we never could have done in-house.

VMK was supposed to be a one-year promotion for Disneyland’s 50th. It got so popular that three years later– the problem was it was cannibalizing the for-play work that Disney Online was doing with Toontown. It was cannibalizing it dramatically, and the company was saying, “Well, tough s***. It’s selling tickets to the theme parks, and the theme parks make more money than Disney Online.”

So there was a war going on between the company and, you know, different divisions of the company. And eventually, we scaled in, caved, backed down.

If you’d like to find out more about the original cancelled Virtual Magic Kingdom game, consider supporting Pop History on Patreon. We’ll be posting exclusive interviews and behind-the-scenes updates on our projects, including early access to articles in progress.